IFFR – Reclaiming Animation: Jenny Barker on Female Pleasures and Feminist Film Practice

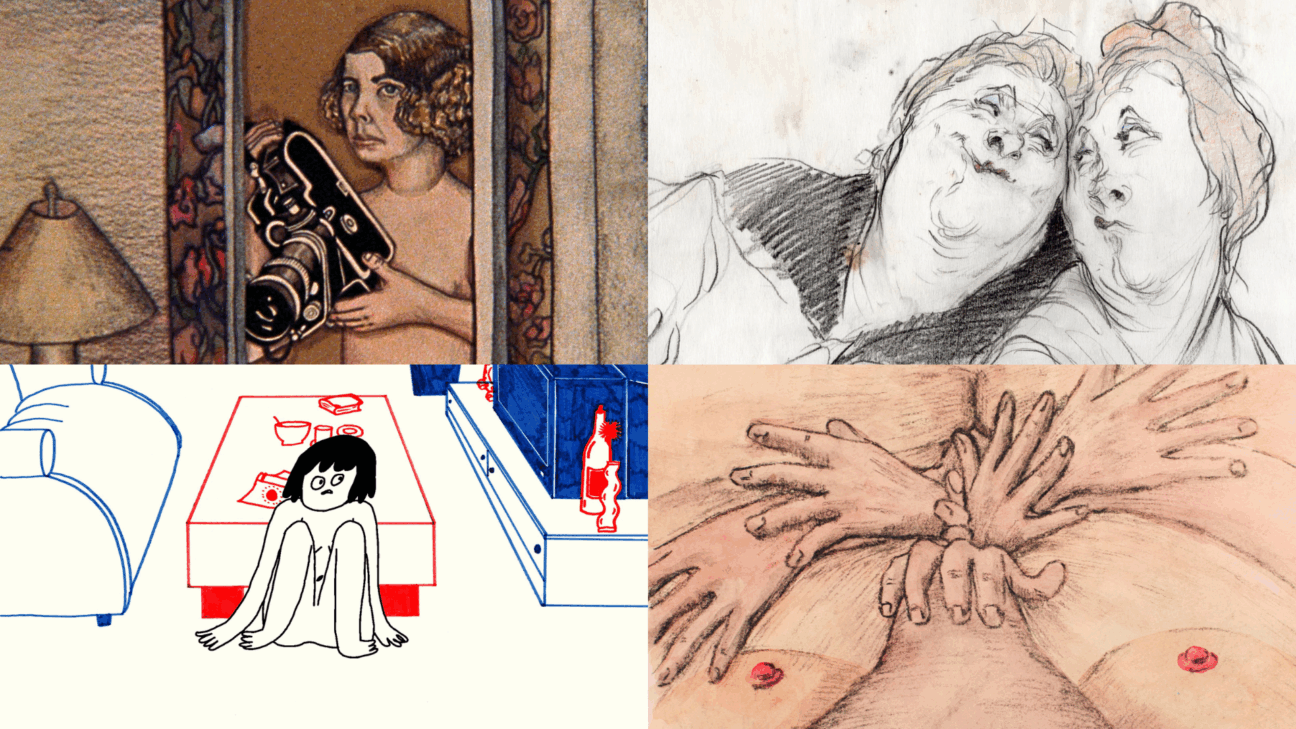

© Crocus, Elles, Pussy, Happy Ending —from Female Pleasures, part of Future Is Now

Tino Manenti spoke with film scholar Jennifer Lynde Barker during IFFR about Future Is Now, a curated program reclaiming feminist film history through animation. In this conversation, Barker reflects on female pleasure, sexual politics, and the radical potential of animated cinema as a space for reimagining gender, desire, and representation.

In recent years, the conversation around representation in cinema has gained more traction, with a focus on the voices and stories that have long been marginalized. Among these, the exploration of female and queer narratives stands out as a powerful force challenging traditional norms and redefining the cinematic language. During this IFFR edition, film professor from Kentucky (U.S.) Jennifer Lynde Barker, together with Olaf Möller, created the curated program Future Is Now. In my interview, Barker contributes to this discourse by sharing her insights into the world of animation and films made by women and gender non-conforming filmmakers.

"When I was an undergrad in the 80s, it was still really difficult to find a lot of women on the syllabus for literature or film, and that has changed a lot over the years, I think, but that was initially why I was interested in it."

When asked about the conception of Future Is Now and the inspiration behind its curatorial direction, Barker reflects on her experience as an undergrad student in the 1980s. At that time, she observed that women were rarely afforded the same visibility or recognition as men when being publicly recognized for their work as auteurs. As she recalls, "When I was an undergrad in the 80s, it was still really difficult to find a lot of women on the syllabus for literature or film, and that has changed a lot over the years, I think, but that was initially why I was interested in it." This early awareness of structural exclusion motivated her curatorial practice today.

For Barker, Future Is Now functions as a deliberately constructed space to reclaim narratives for those who have been historically underrepresented. Structured around different historical periods, forms, and stylistic approaches, the selection of films presented is thought-provoking and confrontational. The one I attended was named Female Pleasures and focused specifically on animation, a branch of filmmaking in which she had observed a persistent lack of attention to women’s work within the field, an absence that directly influenced her initiative. At its core, the program is rooted in the question, "How can cinema serve as a medium to reclaim and redefine narratives around gender and sexuality?”

Within this framework, Female Pleasures, a section of Future Is Now, presents a collection of animated shorts that placed early feminist works in conversation with contemporary films. Inspired by the archival sentiment of early feminist movements of the 1960s and the 1970s while extending their concerns into the present, the program spans contexts such as the US, Canada, Australia, and Europe. Rather than focusing on a single historical moment, it traces how women have continuously contested their structural marginalization, demanded greater representation, and redefined cinematic expressions of desire across generations.

Curious about the close relationship between animation and film history, Barker elaborates on the question, "Why was animation chosen as the right medium to explore female pleasure and sexual politics?” She explains that animation has a distinct advantage in its ability to abstract and reimagine reality. This abstraction allows it to step outside the often simplistic and static male gaze, which tends to objectify the female body, and, at the same time, provides a level of creative freedom that live-action films often cannot achieve. As the professor puts it: “You’re not really dealing with the actual bodies,” which allows the medium to distance itself from the constraints of objectification and become the ideal form to engage with the themes of gender and sexuality in a more introspective and imaginative way.

“Female Pleasures does not oppose pleasure and trauma as something separate or opposite; it consciously reflects on how both could coexist as an entangled experience.”

Each of the shorts presented during the screening appeared to reclaim and reinterpret erotic imagery in its own distinctive manner. Some were designed to unsettle the viewer by alternating between discomfort or pleasure, while others embraced vintage aesthetics reminiscent of earlier feminist visual traditions. Still others adopted a voyeuristic, almost ecstatic approach. The films collectively engaged themes such as prostitution, assault, and systematic patriarchal violence alongside expressions of desire. Within this context, Female Pleasures does not oppose pleasure and trauma as something separate or opposite; it consciously reflects on how both could coexist as an entangled experience.

Barker frames pleasure as a political issue that has often been denied, noting, “It’s something that women have fought for.” She also acknowledges that some of these films were difficult to watch, as in the case of “Granny’s Sexual Life," which explores the painful experiences of women’s sexual lives in 20th-century Slovenia. Yet she explains that animation allows such agonizing topics to be mediated, providing a degree of distance that makes them more digestible while still preserving their emotional impact.

Another film that stood out was “Happy Endings," which challenges viewers to consider the complexities of a sex worker's thoughts on pleasure in unexpected contexts. “It made me reflect on the idea of taking pleasure where you can and the guilt that might accompany it. For instance, if a prostitute feels pleasure in her work, is that inherently bad or good? Is that okay? These are questions that men don’t grapple with, and I wanted to present a spectrum of these experiences.”

Taken together, these works do more than simply portray eroticism. They interrogate the ethical, political, and social dimensions of pleasure itself. Hence, Barker’s curation aims to challenge viewers to confront their own preconceptions and biases and shows how pleasure can be both empowering and fraught, a site of resistance as much as of vulnerability.

© Granny’s sexual life, film still

In exploring female pleasure through works from the mid-to-late 20th century, Barker observes that these films often dealt with heteronormativity and the ways in which women responded to their own desire. "Crocus" offers a humorous and affectionate portrayal of a woman discovering her sexuality, set, for the most part, within the single, static environment of a bed. The film playfully juxtaposes her sensual and maternal roles, using the casualness and randomness of objects floating around the room to reflect the unpredictability and complexity of her experience.

Similarly, “Bianca Putica. A Girl in Love," shot in black and white, presents a campy, earthly, and spiritually charged woman, commanding the space as she stands dominantly, while her male partner lies naked in bed in a passive, gazing position. Both shorts disrupt conventional representations of heterosexual love, presenting moments that diverge from normative depictions of sexual and relational dynamics. As Barker observes, these works offer “early examples of women reimagining their space and their relationship to men,” demonstrating how 1970s filmmaking enabled female filmmakers to experiment with desire, power, and agency.

“I would love to see more exploration of this kind of... just female spaces that are not really engaging with anything outside of them."

© Blanca Putica. A Girl in Love, film still

As the interview concludes, the conversation turns to the future direction of feminist erotic cinema. She points to "Pussy,” a contemporary short from 2016 that was also included in the program, as a significant example. The short depicts a young woman’s journey of self-love and exploration through masturbation. Reflecting on the film, she says: “I would love to see more exploration of this kind of... just female spaces that are not really engaging with anything outside of them." Animated shorts like Pussy playfully imagine a woman being friends with her own body and that vulva as an active presence, asserting agency independently, driving the action, and creating interruptions and comic momentum. In doing so, they step outside the idea that sex is strictly erotic and sensual and instead promote an understanding that sex is really about “sensation, experience, relaxation, and comfort.”

Overall, Female Pleasures reminds us that cinema has the potential to create spaces where all stories can be told and heard. By stepping outside societal and sexual constraints, the program becomes a collective political act of exploring pleasure, one that invites us to reconnect with our own bodies and with others as part of the shared human experience.