IFFR — Thana Faroq and the Unfinished Work of Return in Imagine Me Like The Country of Love

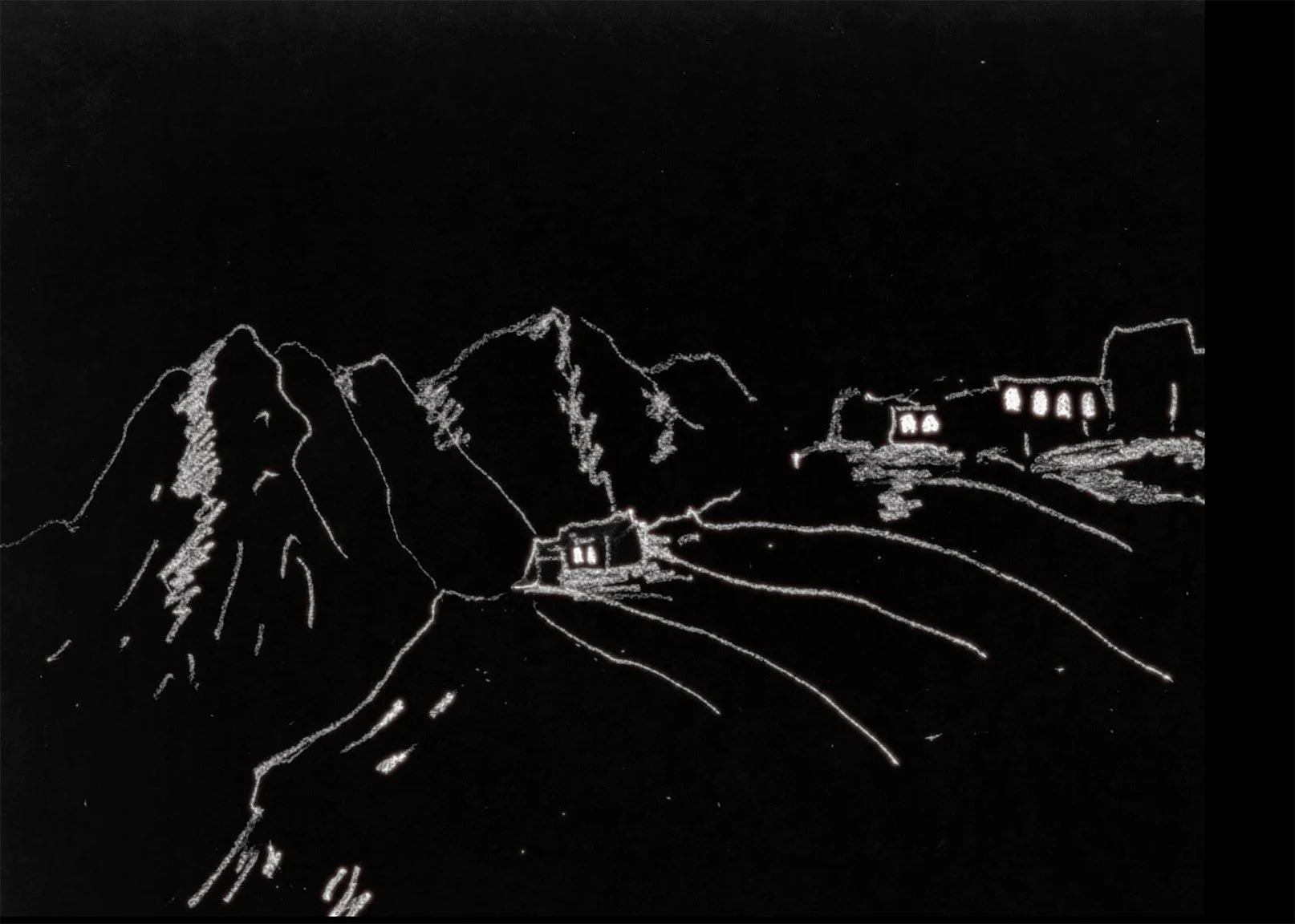

© Imagine Me Like The Country of Love, film still.

At the International Film Festival Rotterdam, Liza Kolomiiets spoke with Thana Faroq about Imagine Me Like The Country of Love (2026), reflecting on memory, displacement, and the experience of inhabiting two homes at once.

“What happens when we disturb the memories we leave behind?” asks Thana Faroq in her debut short film Imagine Me Like The Country of Love, premiering at IFFR. For the Yemeni artist, currently based in the Netherlands, the project began by revisiting her homeland after ten years of living in exile.

In the film, Faroq offers an intimate reflection on displacement, shaped by the tension of inhabiting two homes at once and fully belonging to neither. Imagine Me Like The Country of Love unfolds from this suspended position, where return does not fully restore familiarity, complicating it instead.

“The film moves across spaces under visible constraint, echoing partially inaccessible places that exist in parallel realities, elsewhere.”

With practice rooted in photography and writing, Faroq gracefully expands her artistic language, combining familial photo archives, recordings from Yemen and the Netherlands, animation, and writing. The film moves across spaces under visible constraint, echoing partially inaccessible places that exist in parallel realities, elsewhere. Simultaneously being “here” and “there,” hearing the voices of loved ones who remain geographically distant, the film closely mirrors the lived experience of separation and longing. Presence becomes fractured and stretched across locations that never fully align.

Throughout the film, memory is never treated like a stable archive waiting to be reopened. Faroq speaks of memory as a texture that can be disturbed, even shocked into motion, particularly through the act of return. “So at that time I didn't think that I would make a film, to be honest, I just knew I had the urgency to do something,” says the artist. What began without the intention of becoming a film emerged through intuition. Unable to photograph freely in Yemen, she wrote, recorded, and filmed whatever was possible, guided by waves of anger and grief that arrived unevenly.

Grief, she explains, never appears in the form of a single event, but as a recurring condition, shaping both the process and the form of the work. Fragmentation becomes a stylistic choice as much as a necessity, as emotions resist linearity. Without a hierarchy, writing, sound, animation, and archival images coexist equally in carrying meaning, each insufficient on its own.

At the same time, this lack of a clear media power structure and fragmentation introduces a productive tension. It allows grief and memory to remain unresolved; however, it also demands an active viewer, one willing to assemble meaning with no reassurance of narrative continuity. The film risks opacity, yet it is precisely within this risk that its emotional precision emerges.

The minimalistic chalk animation enters the film as a mediator between past and present, prompted by the realization that return alters the memory instead of simply reactivating it. “While I was there in Yemen, I started to remember things that I completely forgot, I didn't know they existed in my life in the first place,” explains Faroq. The animated drawings draw from this unstable ground, where memory is reconstructed rather than retrieved.

This instability extends to the family archive, particularly photographs of women gazing directly at the camera. In a context where photographing women in public had become impossible, these images take on renewed weight. Revisiting them becomes an act of reclamation, restoring visibility and intimacy that distance and restriction have eroded. Yet this return to the archive also carries the pull of nostalgia. The images extend comfort and connection, simultaneously underscoring what can no longer be accessed or repeated. Reclamation and loss remain inseparable.

“Images of the Dutch landscape anchor the viewer in the present; voices and sounds from Yemen intrude, overlap, and persist.”

If memory fragments the film’s visual structure, sound becomes the element that binds its temporal layers. Return, in this sense, is never complete and never singular. Images of the Dutch landscape anchor the viewer in the present; voices and sounds from Yemen intrude, overlap, and persist. Faroq frames this dissonance as central to the diasporic experience. One can be fully present in the Netherlands, attending language classes and building a life, while the emotional and sonic world remains tethered elsewhere. Time slides between Yemen, the Netherlands, and the deeper past preserved in the archive, producing a layered temporality that mirrors divided attention.

Throughout the conversation, Faroq resists formulating the work as an explanation of war or national history. She is clear that the film has no aim to educate or provide an exhaustive context. It operates through affect, where loss, attachment, belonging, and disattachment are presented as conditions that exceed geography and politics. For viewers unfamiliar with Yemen’s history, this affective approach offers an opening for emotional recognition without prior knowledge. At the same time, it establishes a boundary, as the film refuses to guide the viewer toward understanding, nor does it translate experience into clarity. Confusion, discomfort, and partial connection are left intact.

This refusal of explanation extends to the film’s engagement with resilience. At one point, the artist’s voiceover remarks that she hates poetry, a statement that initially appears contradictory given the lyrical quality of her writing. “I felt I was so tired that I hate resilience. So I gave it a name, and it was poetry,” says Faroq, hinting at the expectation of handling endurance with grace. Imagine Me Like The Country of Love resists presenting resilience in redemption, remaining with the fatigue of survival.

© Imagine Me Like The Country of Love, film still.

In this way, making the film itself is a form of continuation and healing. Faroq speaks openly about the process sustaining her more than the moment of exhibition, admitting that “the making was even much better than screening it.” Creation becomes a way to remain in motion when belonging feels suspended, resisting paralysis rather than promising closure. “As long as we’re creating anything, we’re fine,” she reflects, whether through words, images, or film. Making permits movement without certainty, a way of staying engaged even when clarity remains out of reach.

“Exile is neither resolved nor reconciled, leaving the viewer with incompleteness, a condition to inhabit.”

This commitment to process shapes the film’s ending, which deliberately refuses resolution. Faroq describes becoming “comfortable with being uncomfortable,” and the film adopts this stance. Exile is neither resolved nor reconciled, leaving the viewer with incompleteness, a condition to inhabit. The film asks for patience, attentiveness, and emotional labor, inviting the viewer to sit with fragmentation despite discomfort.

Imagine Me Like The Country of Love does not insist on identification or understanding; it allows for distance, hesitation, even refusal. What it offers instead is a space in which home persists unevenly, in fragments held together through memory, making, and the fragile, insistent persistence of connection.

Liza Kolomiiets is a Ukrainian researcher and critic based in the Netherlands, working across film, fine art, and media. Her work focuses on themes of displacement and exile, while her curiosity extends to a wide range of visual forms and artistic expressions.